Cervical Spinal Instability and Treatment

Instability is when the spine or neck cannot maintain its correct shape and movement. It’s defined as ‘the inability of the spine under normal loads to maintain its normal movement without incapacitating pain, neurological damage or irritation or neck deformity’. Assessment is not always straightforward and involves a careful history alongside examination with X-ray or MRI scans.

Another way to describe instability is “an excessive range of abnormal movement for which there is no protective muscular or ligamentous control.” Stability refers to body’s ability to control the entire range of motion around that joint. Because an unstable segment is less stiff and less resistant, aberrant movement within the spinal column occurs even under minor loads—thereby altering both the quality and quantity of motion.

Stiffness and instability are not the same!

It’s important to understand that stiffness, or the degree of movement available in the spine, and instability are very separate entities. The neck can be stiff, with little range of movement, but within the available range of movement the spine can be stable and pain-free. There are many healthy people with tight necks who can function well, where there is stability of joint movement within their available range. They may have long since been used to using wing mirrors to reverse the car and turn their whole body when looking round, but otherwise their necks are stable and supportive.

It’s also possible that a stiff neck may have instability at one joint, but be hypomobile or rigid in the joints above and below the instability. Conversely there may be muscle spasm or guarding preventing the neck from moving, so the result is a very stiff neck with instability.

Likewise a hypermobile or over-mobile neck can be stable with controlled movement, or be unstable. In fact the hypermobility is possibly more likely lead to instability, if there is a lack of ligamentous and collagen support.

Overall there can be a modern thinking that flexible (or hypermobile) is better. I believe that a balance is required; too stiff or over-flexible, both can be harmful. Healthy joints exist when they are moving freely with relaxed muscles balanced in their available range, be the range of movement small or large.

The upper cervical spine is vulnerable to instability

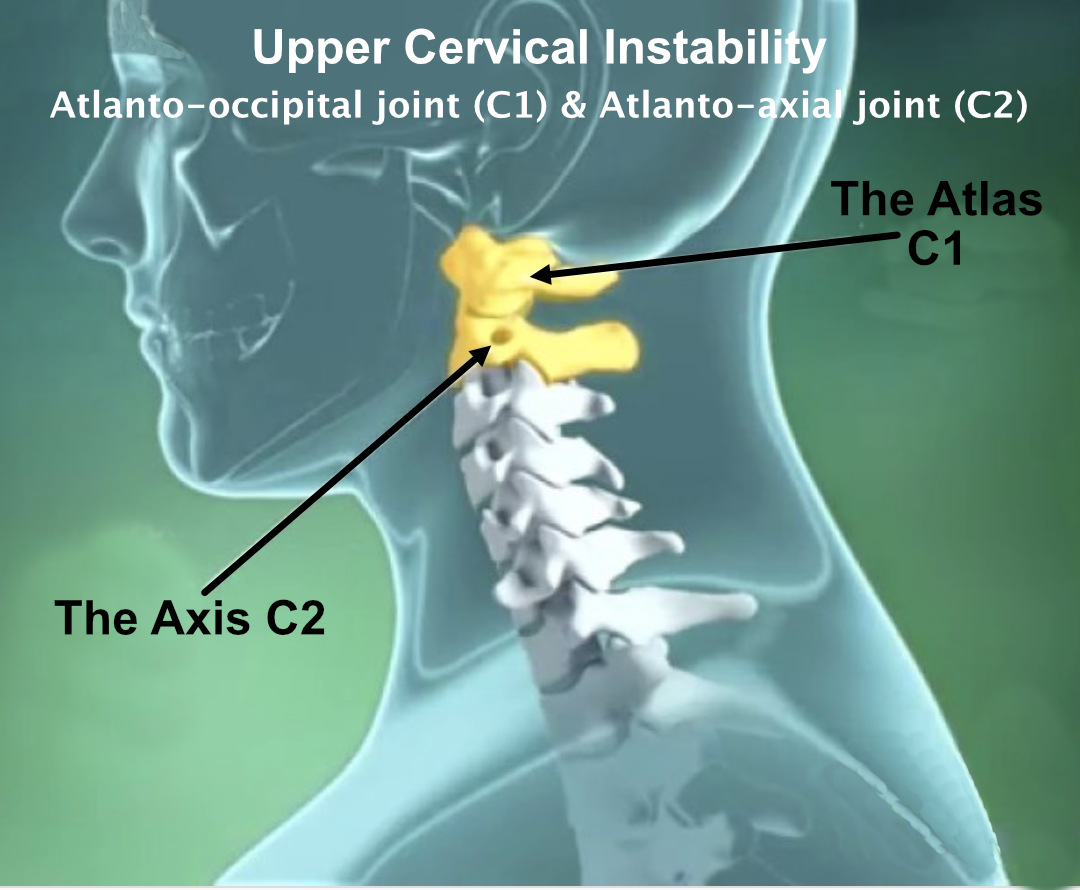

The cervical spine allows for huge mobility at the sacrifice of stability, and is therefore vulnerable to injury, particularly if there is previous trauma, altered spinal curve, or predisposing medical conditions. The cervical vertebrae are protected and stabilized by ligaments both internally and externally and the surrounding postural muscles and produce cervical motion and also feed proprioceptive information from the spinal nervous system to the brain. The upper two cervical joints, the atlanto-occipital joint at C1 and the atlanto-axial joint at C2, however, are designed to allow for a huge range of movement, so are vulnerable to injury and instability especially with high forces to the head which is relatively heavy.

Causes of Spinal Instability

- Trauma – Either one major trauma or fracture, car accident, sporting injury

- Flexion-extension injuries like a whiplash can cause ligamentous disruption with instability.

- Repetitive Microtrauma ie repetitive force in a rugby scrum, or continual heavy lifting

- Recent neck/head/dental surgery.

- Past history of neck dysfunction or trauma

- Degenerative disease of the spine or facet joints

- Central or lateral disc herniation

Arthritic or Medical causes of spinal instability

Inflammatory arthritis such as Rheumatoid arthritis or Ankylosing Spondylitis, due to the progressive joint destruction, most common at the C4-C5 level

Conditions with lax ligaments or weak collagen: Down’s syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos, Grisel, Morquio

Guillain-Barré syndrome

Cervical spondylosis, canal stenosis

Infections such as discitis, osteomyelitis, etc.

Clinical Presentation/Examination for Instability

- Inability to hold prolonged static postures, maybe with neck pain

- Head feels ‘heavy’, tiredness and difficult to hold the head up better for neck support with hands or collar

- Frequent need for self-manipulation; see Joint Manipulation Misconceptions

- Feeling of instability or lack of control, shaking or tremors

- Frequent recurring episodes of acute sharp pain

- Relief when taking weight off the spine and neck lying down

- Joint sounds – Catching, clicking, clunking, and popping sensation

- Small trivial movements cause symptoms

- Muscles feel tight or stiff

- Psychological trauma, apprehension, or fear of movement

- Temporary improvement with clinical manipulation

- Tenderness with muscle spasms in the neck, suboccipital and thoracic spine

- Referred pain in the shoulder, upper back or headaches

- Cervical radiculopathy

- Decreased cervical lordosis – shown on x-ray

Physical examination of neck instability

- Poor coordination/neuromuscular control

- Lack of smooth joint movement. Possible segmental hinging, pivoting, or fulcruming

- Catching movements, jerkiness and juddering with joint locking or subluxation

- Hypomobility in certain neck directions and in the upper thoracic spine

- Muscle spasm and protective guarding

- Instability that is palpable in certain movements or at a specific level – hypermobility with a soft end-feeling in motion palpation

- Decreased cervical muscle strength

- Catching, clicking, clunking, popping sensations felt or heard on movement examination

- Apprehension, fear or unwillingness from the patient to allow the neck to be moved

- Pain with joint-play testing, either in static or motion palpation

- Reduced neck muscle strengths on active testing multifidus, longus capitis, longus colli

- Instability tests: Sharp-Purser, Transverse Ligament Stress Test but can be nonspecific

Diagnosis of Cervical Instability

Cervical instability is a diagnosis based primarily on a patient’s history and reported symptoms.

X-rays are used, however dynamic imaging, MRI, CT and studies with contrast are often necessary to detect instability. The studies and work with Osmira at the Anglo-European college of Chiropractors in Bournemouth, using low level fluoroscopy to map movement patterns of the vertebrae, creating a ‘moving x-ray’ of the vertebral bodies, will undoubtably with time bring huge progress and shed light on our understanding of instability.

X-Ray diagnosis of instability

- Lateral neutral, flexion and extension or may be required

- Segmental kyphosis greater than 11 degrees

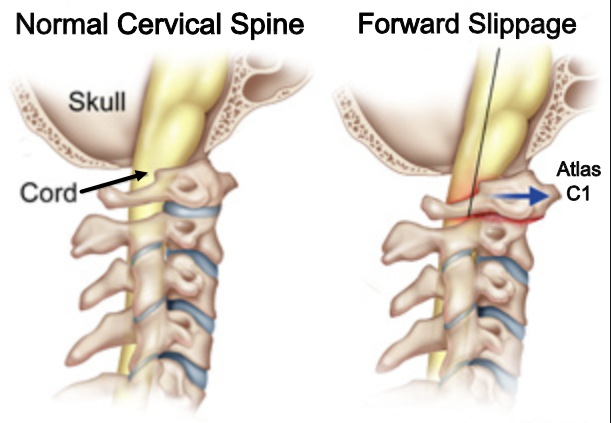

- Slippage of one vertebra on another; forward anterolisthesis or backward retrolisthesis of one vertebral body > 3.5 mm on another

- Spondylolisthesis, or change in pedicle length

- Narrowing of the intervertebral foramen and loss of disc thickness

- An abrupt apparent change in pedicle length

Anteroposterior x-rays with lateral bending:

- Lack of lateral flexion to one side

- Decreased vertebral rotation and tilt with aberrant movement patterns

- Misalignment of the spinous processes and pedicles

- Lateral translation or shift of vertebrae due to abnormal rotation

Assessment of upper cervical ligamentous instability is difficult and needs to be considered on an individual basis, taking into account the patient’s history, examination results, scans and any underlying medical conditions.

Neck questionnaires and outcome measures

These three questionnaires are specific and valid instruments to evaluate the neck pain and dysfunction: Neck Disability Index, Neck Bournemouth Questionnaire and Neck Pain and Disability Scale.

Treatment of Spinal Instability

Severe instability may need medical treatment. With a fracture, for example, surgical treatment may be required with stabilisation of the spine to allow the bones and ligaments to heal to prevent any further injury.

The difficulty is to understand when conservative treatment can be given, or surgical treatment for spinal instability is required. Lack of consensus about the current definitions of spine instability, and lack of understanding of spinal biomechanics and X-ray instability and the clinical presentation makes the diagnosis and treatment spine instability more of a challenge.

Old treatment methods for spinal instability like traction, casts, immobilisation and prolonged bed rest are replaced now with cervical fixation if required and early introduction of safe movement and mobilisation as early as possible, which has been shown to greatly assist with ligament healing. Conservative treatment is indicated when it does not damage neurological structures or cause nerve irritation, with the aim of improving movement and reducing muscle spasm & pain, thereby helping patients to resume active life as soon as possible.

Chiropractic manipulation for spinal instability

Spinal manipulation can be performed on the tight, locked, restricted or hypo-mobile vertebrae above or below the level of instability, which reduces the mechanical stresses at the level of clinical instability. Care must be taken to monitor the response to the manipulation to check if there has been any aggravation, excess rebound muscle spasm or neurological reaction. However, done with care, manipulation can make a huge improvement and stimulate healing.

A Chiropractic Study in 2016 for treatment of upper neck instability showed clear benefits; see more information below.

Postural and movement training

Reduces stress and pressure on the neck and upper back, helps reduce fatigue from long periods of sitting or working and teaches patients how to manage their condition, learning to vary activities, take breaks and avoid aggravating stresses and strains. The Alexander Technique is ideal for this learning as it focuses especially on the tension in the upper neck and base of the skull with upper cervical vertebrae and Suboccipital muscles.

Massage and Myofascial release techniques

Muscle releasing to the neck and base of the skull can be very tender whilst being performed, but can be varied and done more gently depending on the patient’s tolerance. The deep muscle releasing techniques are gentle and non-invasive so are highly unlikely to aggravate or worsen the instability and can be very beneficial and help greatly to release the muscle spasm, improve neck mobility and reduce the symptoms.

Muscle strengthening exercises for spinal instability

I personally do not like giving muscle strengthening exercises for the neck for various reasons. However there is a place for all different treatment approaches and sometimes these can be beneficial. They must be done carefully with caution and slow progressive increase. One of my main concerns, apart from lack of patient compliance, is that the exercises only worsen the condition and are difficult to perform. They may give pain and above all do not help improve the strength in the deeper core postural muscles, but only serve to over-stimulate the over-active external muscles that are already in pain or spasm. Care and caution must be used.

Neck stretching and range of movement exercises for spinal instability

Once again, I personally do not like giving movement exercises and muscle stretching exercises for the neck. However, as with strengthening exercises, no one treatment is right for everyone and sometimes these can be beneficial. They must also be done carefully with caution and slow progressive increase.

There is a huge danger that patients will get into bad habits of stretching repetitively, with the feeling that it helps, albeit very temporarily. I have lost count of how many clients attend with the constant habit of stretching the neck, shoulders or arms, which simply becomes a repetitive strain! I urge caution with this.

Neck Pain & Instability Helped by Chiropractic, According to 2016 Study

A study published on 30th October 2016 by International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine (IJCEM) indicated Chiropractic can help patients with upper neck instability.

Instability of the atlantoaxial joint (C1-2) can be serious and lead to neurological problems (The hangman’s fracture is the most well-known extreme injury). 128 patients with pain and atlantoaxial instability shown on X-ray were divided into two groups of 64. Control Group 1 was treated with a form of traction. Group 2 was treated with chiropractic treatment for up to 1 month with a 1-year follow-up evaluation.

Conclusion of the study: the results suggest that chiropractic treatment for treatment of upper cervical instability was more effective than traction with a lower reoccurrence rate after 1-year.

Key:

- Cured: Main pain and tenderness were disappearing. X-rays showed normal C1-2 joint.

- Marked effective: The patient’s main pain was disappearing.

- Effective: The patient’s main pain was partially relieved.

- No Effect: The patient’s main pain remained, X-rays showed no change.

Further reading

| Group 1 (control) | Group 2 (Chiropractic) |

|---|---|

| 25.0% Cured | 43.7% Cured |

| 28.1% Marked Effective | 31.3% Marked Effective |

| 25.0% Effective | 20.3% Effective |

| 21.9% No Effect | 4.7% No Effect |